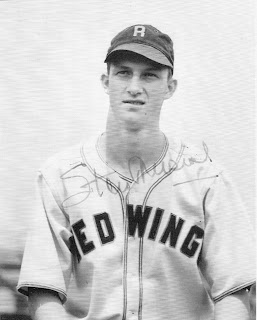

Had the opportunity to interview both Stan Musial and Earl

Weaver a few times through the years, and they both lived up to their

reputations. Stan the Man was gracious and kind as advertised, a real

salt-of-the-earth guy. And the Earl of Baltimore was a tad cantankerous, but

still managed to spin some interesting tales. (Ones, I might add, that were

peppered with expletives that were a colorful part of Earl’s vocabulary.)

Both Baseball

Hall of Famers, who died over the weekend, once donned the Red Wings flannels,

and remain two of the franchise’s most beloved alums.

While

researching Silver Seasons, the

history of the Wings that I co-wrote with Jim Mandelaro, I came across an

interesting anecdote about Musial’s Rochester arrival. After stashing his paper

bagful of clothes and personal belongings into his locker (he was too poor to

afford a suitcase), Musial pulled on his uniform and headed for the batting cage.

The young hitter with the awkward-looking,

corkscrew stance lashed line drives all over the field. But a big-league scout was

unimpressed. He turned to Wings manager Tony Kaufmann, shook his head

disapprovingly and said: “He’ll never make it up there. Not with that stance,

he won’t.”

While

researching Silver Seasons, the

history of the Wings that I co-wrote with Jim Mandelaro, I came across an

interesting anecdote about Musial’s Rochester arrival. After stashing his paper

bagful of clothes and personal belongings into his locker (he was too poor to

afford a suitcase), Musial pulled on his uniform and headed for the batting cage.

The young hitter with the awkward-looking,

corkscrew stance lashed line drives all over the field. But a big-league scout was

unimpressed. He turned to Wings manager Tony Kaufmann, shook his head

disapprovingly and said: “He’ll never make it up there. Not with that stance,

he won’t.”

Kaufmann

was incredulous. Sure, Musial’s stance was ugly. (“He looks like a kid peeking

around the corner to see if the cops are coming” was the way one player

described it.) But his swing was a thing of beauty, and was enough to convince

Kauffman that the son of a Polish immigrant zinc miner from Western

Pennsylvania would not only make it, but become a Man among boys.

Musial

spent just 54 games with the Wings before being promoted to the St. Louis

Cardinals. His Rochester stint included 10 doubles, four triples, three home

runs, 21 runs batted in and a .326 average. His torrid hitting continued in the

big leagues as he batted .426 in 12 games with the Cardinals. Musial told me in

a 1987 appearance in Rochester that he fully expected to be reassigned to

Rochester the following spring. Instead, he stuck with the big club, and you

know the rest of the story: Seven National League batting titles, 3,630 hits, 475

home runs, a .331 career batting average and a first-ballot induction into the

Hall of Fame.

I

wonder whatever became of that not-so sage scout who doubted Musial’s

unorthodox stance. I also wonder what might have happened if Musial – who originally

was signed as a pitcher and who went 18-5 in the Florida State League – had not

injured his shoulder while diving for a ball in 1940. Would he have become a

Hall-of-Fame pitcher? Or would he have faded into oblivion like thousands of

other ballplayers?

Lastly,

I wonder how much more appreciated Musial would have been had he played for the

Yankees or Dodgers or Red Sox. He remains one of the most underappreciated

superstars in sports history, overshadowed by contemporaries such as Joe

DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays.

It's cliché

and risky to say that Musial was an even better person than he was a

ballplayer. But, in this case, I believe it’s true. I’ve never read or heard a

disparaging word about him. He was beloved by his peers and fans. He clearly

wasn’t just the Man on the diamond.

***

Weaver’s

ties to Rochester were much stronger than Musial’s. Earl spent two seasons

managing the Wings, guiding them to a pennant in 1966 and a second-place finish

the following summer. That led to his promotion to the Baltimore Orioles, where

he began a Hall-of-Fame managing career that saw him win four American League

pennants and one World Series title.

Earl was known for being a master tactician and a pugnacious competitor. At 5-feet, 6-inches tall, he was shorter than all of the players he managed and most of the umpires he verbally sparred with. Spurred on, in part, by a Napoleonic complex, Weaver took guff from no one.

There’s

a great story about a 1963 ejection from a game in Charleston, W.V. when Weaver

pulled the third base bag from the ground and carried it into the clubhouse and

locked the door. Apparently, the grounds crew couldn’t find another base, so

the umpire sent the clubhouse boy to retrieve the bag from Earl. Weaver gave

the clubbie the bag after he was told that the umpire was about to forfeit the

game in the other team’s favor.

Weaver

wound up being ejected 21 times during his two seasons skippering the Wings and

91 times with the Orioles. He was known to turn his cap backwards, so he could

get face to chin with the umpire. He loved kicking dirt on homeplate after he

had been given the thumb. Umpires hated his histrionics, but fans loved it;

they thought it was great entertainment.

The

infamous feud between Weaver and Hall-of-Fame pitcher Jim Palmer has its roots

with the Red Wings. A year after beating Sandy Koufax during Baltimore’s World

Series sweep of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Palmer developed arm problems and was

sent to Rochester on a rehab assignment. In his first start for the Wings, the

Orioles ace was cruising along with a 6-0 lead against the Bisons at old War

Memorial Stadium in Buffalo before running into control problems in the fourth

inning. He wound up walking the bases loaded and after throwing two balls to

the next hitter, Weaver stormed out of the dugout to have a conference with his

pitcher. “Throw the (bleeping) ball over the (bleeping) plate,’’ Weaver barked.

“This guy is (bleeping) nothing.”

Palmer

didn’t appreciate Weaver’s tirade, but he grudgingly followed orders. He threw

the next pitch down the pike and the “(bleeping) nothing” – who went by the

name of Johnny Bench – hit the ball over the fence for a grand slam. It would

be the only grand slam Palmer would allow in his professional baseball career. “Earl

Weaver lost all credibility with me at that point,’’ Palmer told me years

later. “I told Earl that the only thing he knew about pitching is that he

couldn’t hit it. I never listened to him again.”

The two

strong-willed men would lock horns on numerous occasions after Weaver became

the Orioles manager, but eventually buried the hatchet.

“Earl

and I actually were similar in many ways,’’ Palmer told me. “He wanted to be

the best manager in baseball and I wanted to be the best pitcher in baseball.

Sometimes we got in each other’s way, but, I’ll say this, when Earl managed, I

can never think of a time when we went into the season and we weren’t one of

the favorites to win.”

Stan

the Man and the Earl of Baltimore certainly were two indelible baseball

personalities. Musial’s line-drive hits, fun-filled renditions of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame”

on his harmonica and his common decency will be missed. As will Weaver’s managing

skills and entertaining theatrics.

2 comments:

Scribe, thanks for taking me back 47 years this summer when I got to sit next to him in the dugout. What great times those were.

What a review here. I just gift a baseball bat to my younger brother in this Christmas that I collected from PIJ. PIJ is great for product and its price. Its always lovely to me. Thanks for sharing this article.

http://bit.ly/matsui-sign

Post a Comment